Blood, sweat and pixels: releasing a mobile game with no experience

In January 2022, we, at Kaspersky, released our first mobile game — Disconnected. The game was designed for companies that want to strengthen their employees» knowledge of cybersecurity basics. Even though game development is not something you would expect from a cybersecurity company, our motivation was quite clear — we wanted to create an appealing, interactive method of teaching cybersecurity.

Over our many years of experience in security awareness and experimentation with learning approaches (e.g. online adaptive platforms, interactive workshops and even VR simulations), we«ve noticed that even if the material is presented in a highly engaging way, people still lack the opportunity to apply the knowledge in practice. This means that although they are taking in the information, it won«t necessarily be applied.

To solve this problem, we decided to create a mobile cybersecurity game that allows players to immerse themselves in familiar and lifelike situations. The main objective of the playable character in Disconnected is to complete a work project choosing the correct cybersecurity-related actions while also maintaining good relationships with colleagues and loved ones. Long story short — you must behave securely, but not at the expense of others.

With a clearly defined goal in mind, we figured, what could possibly go wrong? Nearly everything it turns out. Making a game for the first time presented challenges — let«s talk about the most critical and difficult aspects.

We didn«t understand why we were struggling and even felt incompetent until we came across Blood, Sweat, and Pixels by Jason Schreier. The book gives insights into the inner workings of the gaming industry and showed us that every problem we faced is typical of the game development process, whether a blockbuster like Diablo or a small indie game. We hope our experience will be interesting and useful for companies outside of the gaming industry looking to develop their own game. Maybe it will even help make the game development process a little less overwhelming.

Game development is an art form. No matter how big your initial budget is or how many resources you have, when you start this kind of project you have the idea of creating the best game in the world. This type of thinking is a trap. When we started Disconnected, we planned on making a 40-minute exciting cyberpunk adventure, but we also wanted to make the game as tricked-out as possible. However, we came to a point in the development process where we realized that, with all the enhancements and additional elements, the gameplay duration had ballooned to ten hours and it wasn«t even finished yet. This, combined with issues with the developers, has led us to a year«s deadline overdue.

How did we get there?

A game isn«t interesting if the player has no autonomy or control over the end result. We wanted players to see that their actions affect the plot and can lead to different outcomes. So, we thought up four different endings of the story: from the best possible, where the main character manages to save their company while maintaining good relations with others, to the worst, where the character faces catastrophic failures on all fronts.

Another aspect that made development more difficult was our decision to implement a set of built-in interactive elements to mimic the digital tools we use in our everyday lives. Such elements included browsers, mobile apps and messengers, which characters could use to help solve cases throughout the plot while simultaneously practicing related cybersecurity rules. For example, there is a password recognition module where the character has to come up with a password, enter it and remember it. If they forget this password, they have to go to technical support and lose valuable time for completing the project. Adding this pretty simple action to the game required a whole separate subsystem for its development.

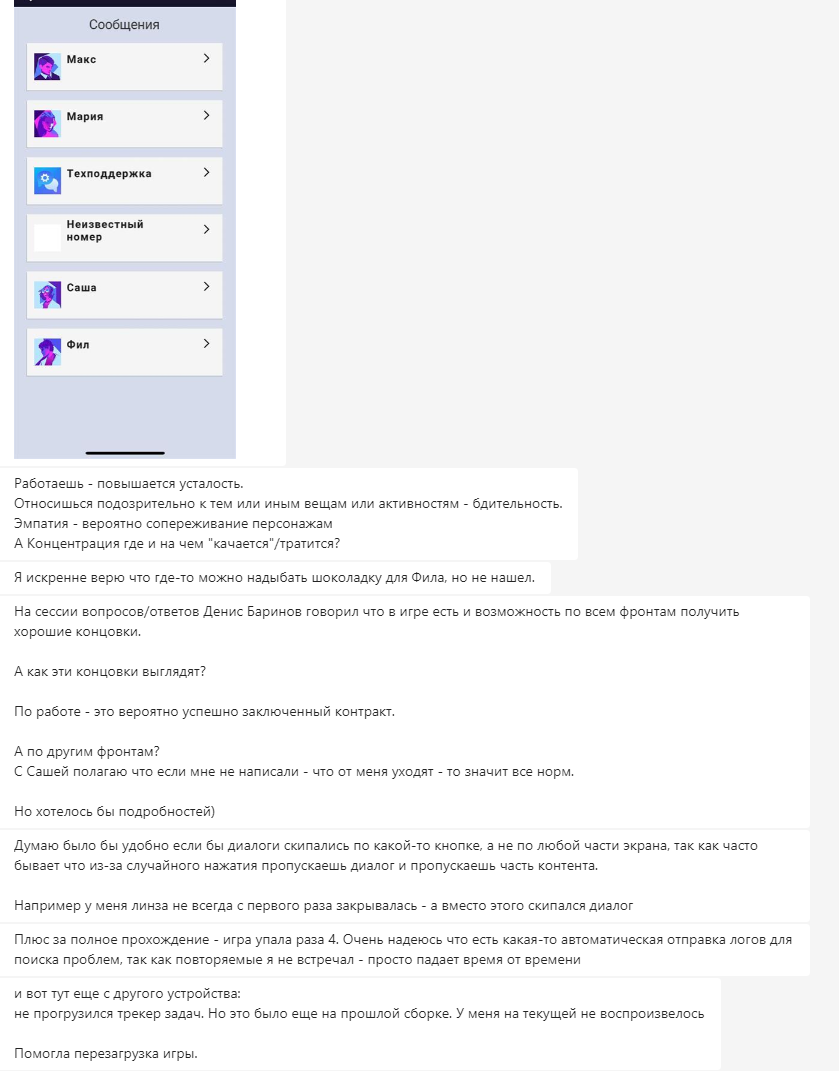

Messenger, mail and task tracker…modern people need these tools, as do the game«s characters

Everything worked great when our developer created these elements separately, but when they were assembled, the interactive modules clashed. It was impossible to finish playing the game because of bugs. For example, the game would crash after pressing the built-in application buttons. The developer wasn«t able to fix old bugs, meanwhile, we kept finding new ones. At a certain point, the developer asked us to slow down and stopped responding to our emails for a while. Initially, we treated this with understanding, however, with yet another broken version of the game and yet another excuse, we started to feel that the project was getting out of control. As we came to realize this and started thinking of ways to save the game, the developer admitted that their team couldn«t fulfill their commitment and would abandon the project. This happened at the final stage, just a few months before the game«s release.

Source.

Why didn«t we notice the incompetence of our contractor earlier?

To understand this, we need to talk about the industry in general. According to our experience, almost all game developer companies, at least in Eastern Europe, unequally subdivide into two parts: the smaller is represented by highly skilled professionals and the larger consists of inexperienced amateurs. Those with the experience won«t work on an indie game because the tasks and budget don«t meet their expectations. The amateurs are not an option because you don«t want to risk your project in the hands of someone vastly inexperienced. The challenge is then to find a contractor that is competent enough to handle your game but is also interested in working beyond big mainstream gaming projects.

Our first contractor seemed like the perfect option — a small, new company founded by people well known as brilliant specialists in the gaming industry. Although they didn«t provide us with a large portfolio of their own completed projects, big names along with recommendations from their employers assured us that we could trust what seemed to be a promising team. So, we placed our confidence in them and left them to develop the project in alignment with our goals and objectives. In the beginning, the team performed well and we enjoyed working together. Some of us even joked that there must be a catch because communication with a contractor couldn«t be so smooth. Because Kaspersky doesn«t specialize in game development, we didn«t have our people check if the technical part was going right until we got an assembled version.

After the first developer gave up, we launched a new tender to find another contractor, which proved a challenge because of the industry subdivide mentioned above. We hardly managed to gather enough competing offers from potential suppliers. So, we ended up signing a new contract with Coderaptor, a company that we had already worked with on our VR project. These guys have a proven track record of expertise, but redoing someone else«s code is much more complicated than developing a game from scratch. Especially if the code is not systematized and is written on outdated software (another unpleasant surprise).

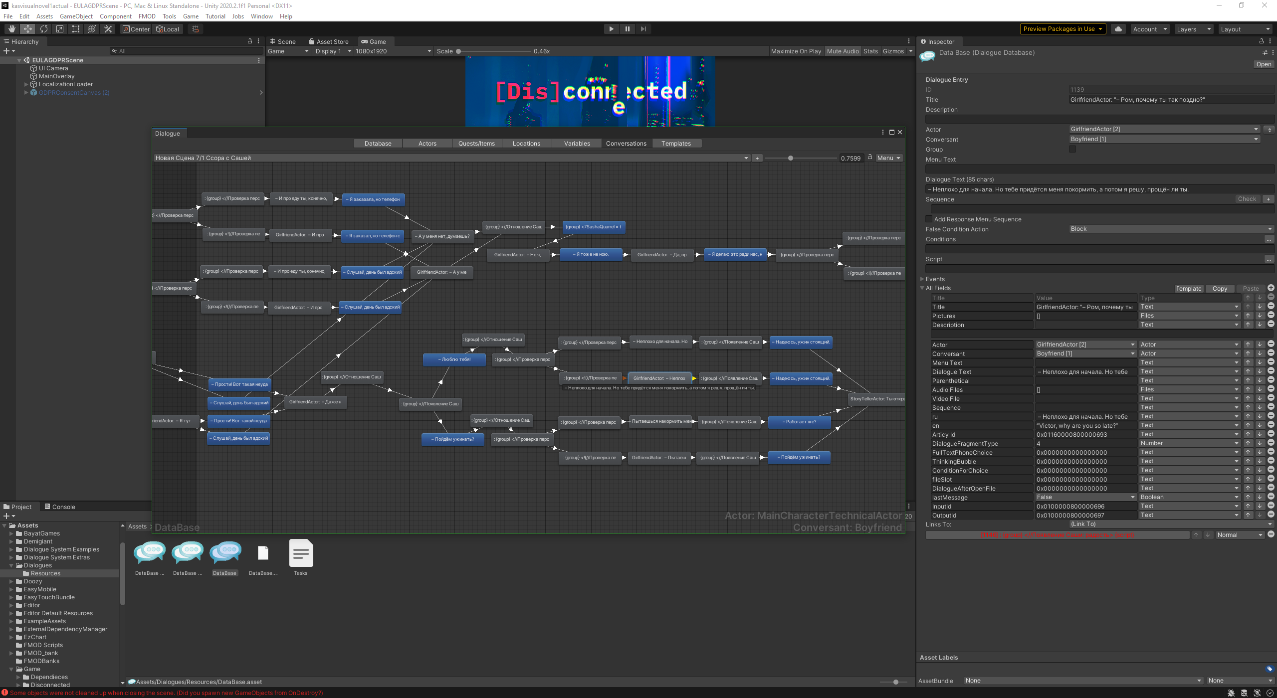

We chose Unity game engine to create a structure of the game

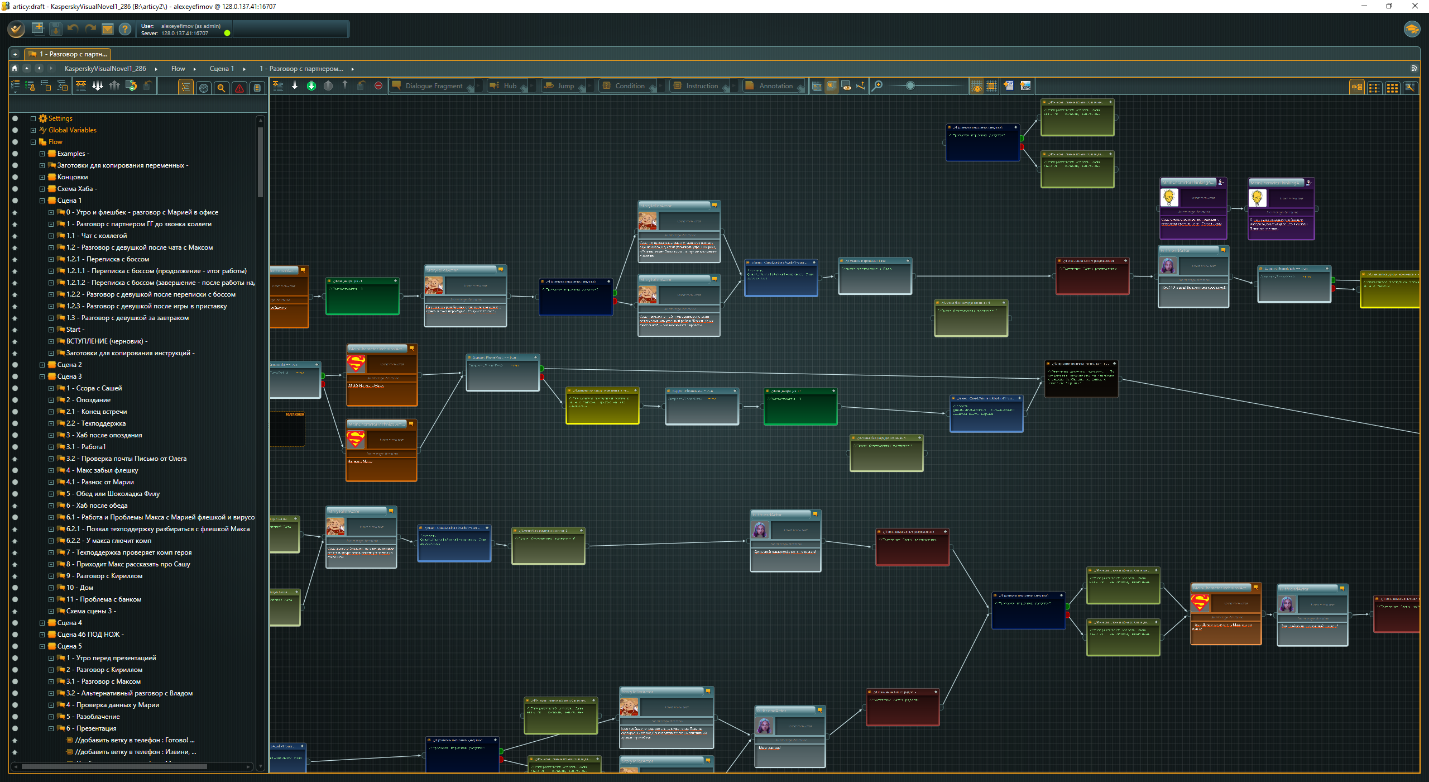

Articy helped us to implement interactive storytelling

Guys from Coderaptor not only had to complete the game«s development but also had to restructure the body of the entire game«s code. To ease and speed up this process, we had to abandon almost half of the modules and significantly shorten the gameplay (it was six times longer in the beginning). All of this forced us release the game almost a year later than the planned release date.

It is boring

When you start a gaming project to create an engaging experience that teaches the basics of cybersecurity, but the final product can«t even engage your colleagues who work in the field, there«s a problem. When our team tried to play the first reassembled version of Disconnected, it was clear that something was wrong.

After the new developer helped us fix the main technical issues, we started to show the game to other people. They didn«t understand the story or the actions a playable character could take. The plot fell apart throughout the game, game details were useless and some crucial links were missing. This demotivated users from completing their missions.

For example, the main character works for SmartFrames, a start-up that is developing human implants to help people be more productive. This small company wants to make their innovative gadgets accessible to everyone. Globis is a large international corporation that wants to buy the startup and the player must stop them. We missed that a simple acquisition is not going to be perceived by most as an «evil» purpose that needs to be fought against.

Initially, when we worked with the first contractor, there was a narrative designer in their team who was responsible for the plot. However, the storyline flaws, including the lack of character motivation and logic behind their actions were only uncovered when the game was shortened. Since the new team from Coderaptor was only in charge of the technical part of the project, there was no specialist available to help us fix the plot problems and, at this stage, we couldn«t hire a professional screenwriter because that would lead to further delays and budget increases.

So, we became narrative designers ourselves. Our team recreated the plot, rethinking each scene and story arc. We studied the principles of storytelling using resources like Robert McKee«s «Story» to better understand what was wrong with the game«s plot and how to improve it. We looked at other dramatic theories, including Aristotle«s «Poetics,» and the storylines in other games (the principle of a plot structure was inspired by Detroit: Become Human) to learn from and compare the best examples with our product. We discovered that the creation of a game plot is a very interesting process. Even though the game is just pictures and text that pops up on the screen, you get to create a whole new world and determine the laws that govern it.

In only a month we rewrote every chapter of the game in alignment with proper dramatic structure. The plot outlined motivating reasons why a player would want to work towards completing the goals. Supported by logic, the story started to actually engage players. The subsequent feedback from colleagues showed that they had become immersed in our «Disconnected» world. People became more emotionally attached to the game. They wanted to learn what happens in the other possible endings and asked for our recommendations on how to unlock other plot lines.

Translation of the thread:

When you work — fatigue increases

When you are suspicious of some activities — awareness increases

Empathy, I guess, increases when you treat other characters with compassion

And what about concentration? When does this increase or decrease?

I sincerely believe that there is a way to find a chocolate for Phil, but I failed

During the AMA session, Denis Barinov said there is a chance to get good endings on all fronts

What do these endings look like?

I suppose a successfully signed contract is a good ending for work

And what about the other areas?

As for relationships — Sasha seems to stay with my character. I guess this means that this is ok

But I«d like more details