[Перевод] Hell or high water: history of Russian popular science literature

And our homeland’s pushing us For reaching knowledge higher heights.

The available and interesting literature on science is a magic wand that helps the progress not to slow down and move forward. Thanks to interesting science literature, children begin to study voluntarily and with interest, while adults expand their horizons and do not allow the brain to relax. Biology, astronomy and mathematics supplant the saga about the elves and intergalactic ships. But while Western countries' nonfiction was always in smooth progress from Jules Verne to Eliezer S. Yudkowsky, then opposite it experienced both ups and downs in Russia.

The Russian Empire

Until the 19th century, science was considered as a business of elite, and scientific works for a wide range of readers were isolated experiments. But the industrial revolution has changed everything. The role of science in people’s lives has grown dramatically, it has attracted attention, a demand for comprehensible scientific content has arisen. It was also required in Russia: there scientific literature and technical progress were both in stuck.

In the Russian Empire, the state was forced to the press and any publishing little step had to be agreed with censorship committees that were guided by church dogmas. The most popular literature was a low-grade mystic one. The predominate attitude in the society was «you gotta do what you gotta do»: women had to give birth, peasants had to plow, and only the elect were able to study science. Some scientists even believed that profanation of science itself was an evil. But with the development of industry in Russia, a need for comprehensible scientific publications appeared and there were those who took up this risky business.

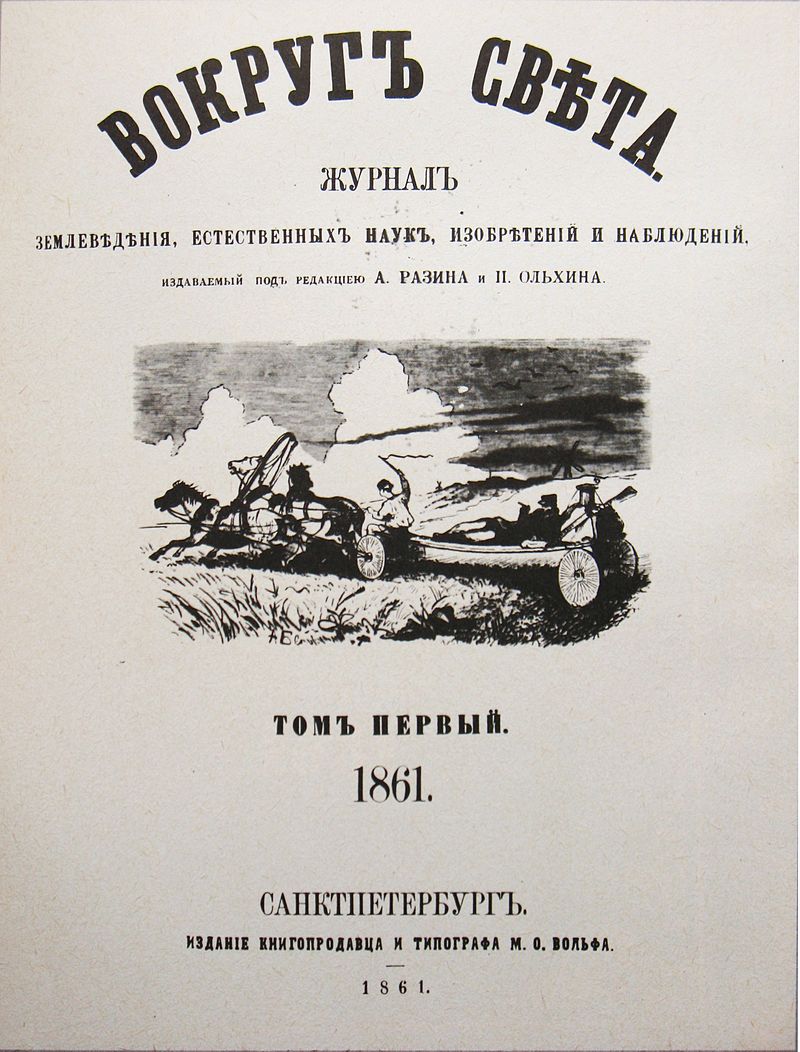

Around the World (Russian: Вокруг Света) — magazine about earth sciences, physical sciences, inventions and observations.

The first sign in 1861 became the magazine Around the World. It published foreign translations and notes on Russian geography. The magazine was being published only for 7 years, and then stopped until 1885. The revived Around the World counted on a low price and compensated for it with the loads of advertising. Gradually, the quality of publications got down to a collection of adventurous and adventure stories. In 1891, the creator of the first Russian media empire, I. Sytin, saved the situation. He formed a new publishing team and made Around the World a mass edition, where information about scientific discoveries and new inventions was printed. The October Revolution made its own corrections to the history of the magazine: the whole Sytin«s publishing empire was nationalized and Around the World was closed. I. Sytin refused the offer made by V. Lenin to lead the State Publishing House and retired.

Priroda (Russian: Природа; literally: Nature) — monthly popular natural and historical magazine for self-education.

The magazine Priroda was even less lucky in its beginning. Zoologist and psychologist V. Wagner, being under the influence of famous Russian writer A. Chekhov, thought up a scientific magazine and almost launched it in the 80s, but the publisher was afraid of problems with censorship. The idea of Chekhov was realized only in 1912. In their address to the readers, the editors wrote that they considered such a format as «the best way to combat with prejudice, with the influence of scholasticism and metaphysics». This attitude was close to many people, and famous physicists, biologists began to cooperate with the magazine; it contained translations of articles by Planck and Einstein. Books were published under the auspices of the magazine, lectures were held. Priroda became a platform for communication between scientists.

Nature and people (Russian: Природа и люди) — illustrated magazine about science, art and literature.

In 1889, publishing house of P. Soikin brought out magazine Nature and People, which instantly became popular. It published information about the latest technical innovations from around the world, articles by pioneer of the astronautic theory K. Tsiolkovsky and participants of the Imperial Russian Geographical Society. In 1901 Yakov Perelman began to work in the magazine, and in 1913 he became the chief editor. His Physics for Entertainment was a huge success with the readers and had positive feedback from professional scientists. It was first book in large and most popular nonfiction series in Russia.

The country of the victorious proletarians

World War I, the Revolution and the Civil War shook Russian society. People were tired of politics: no one read K. Marks, V. Lenin and others same as well. In the same time fiction, classics and scientific books were took away by readers from book stalls. There was a huge demand for self-education, and society needed accessible scientific and technical literature.

Magazine In the workshop of nature (Russian: В мастерской природы) cover.

The Civil War was still in full swing, and in 1919 Ya. Perelman launched the first Soviet popular science magazine In the workshop of nature. After a one-year break, the magazine Priroda resumed its work under the protection of the Academy of Sciences. A little bit later, new magazines appeared: Radio Amateur — 1924, Knowledge is power — 1926, Young naturalist — 1928. Priroda i Lyudi (1927) and Around the World (1927) were reintroduced. Before the creation of a publishing monopoly in 1930, non-fiction publications were actively printed by private publishing houses. Only the press house of P. Soykin published about a hundred books: In the Sands of the Karakum Dezert by A. Fersman, On the Ryukyu Islands by P.Schmidt, In the Heart of Asia by P. Kozlov.

Magazine Nature and people Soviet covers.

The interests of society were strengthened by state projects: enormous Soviet construction projects and forced industrialization required a huge number of qualified personnel and serious advertising. The colleague of V. Lenin and the former member of the Politburo — N. Bukharin was responsible for technical promotion. The magazines Socialist Reconstruction and Science — 1931, Technics for the Youth — 1933 appeared, the magazine Science and Life was reintroduced in 1934.

After the unification of all publishing houses in OGIZ, the largest publishers of nonfiction become ONTI, and DETGIZ headed by popular children’s writer S. Marshak. They published the series Science to the Masses, Technical-constructive series for children, Sciences for Entertainment by Ya. Perelman. As well were published series books by physicist M. Bronstein, historian of antiquity S. Lurie and many other. Soviet popular science literature was exported: What time is it? , Black on white, 100,000 why-questions, Moscow has a plan, A Ring and a Riddle, How a man became a giant by M. Ilin were translated into all European languages and published in the USA.

M.Ilyin books cover. In these books, the author easily explained how technology developed by common words.

The problem was that the young Soviet state did not provide the country with high-quality popular science literature. There was lack of publishing houses, paper, but especially there was not enough authors. Incompetence of censors, orientation to the Soviet leadership and fear of repression hampered nonfiction literature: many topics were banned, and experienced engineers trained in tsarist Russia, journalists and writers became the class enemies with all the tragic consequences.

Soviet began to search for authors among the labors: on December 31, 1931, a resolution «on engaging of the labors in the creation of a mass technical book» was issued. It did not help. In the second half of the 1930s, both ONTI and DETGIZ began to fail gorgeous plans coming from the government. And if ONTI was simply disbanded, then the Leningrad branch of DETGIZ was eliminated. In 1936, the main competitor of Priroda, the magazine Socialist Reconstruction and Science was closed and removed from all libraries, and in 1938 N.Bukharin was shot.

And nevertheless in the USSR there was an organization in which aspiring cadres staid straight. It was the Academy of Sciences. Optician academician S. Vavilov had a dig at popularization of science in the Academy of Sciences. In 1935 he became chairman of the commission of the USSR Academy of Sciences on popular science literature. In 1936 he headed the editorial board of Priroda, and even knocked out Academician T. Lysenko, who was Stalin«s favorite and the killer of Soviet genetics.

Book cover from Akademia nauk USSR to the Stakhanovists series. Ноw the sky was observed before and how it is observed now.

In 1938 the Publishing House of the Academy of Sciences of the USSR launched three series at once: The USSR Academy of Sciences to the Stakhanovists series edited by the President of the Academy of Sciences V. Komarov, on physical sciences, edited by S. Vavilov and a series devoted to agriculture. Despite the growing number of popular science publications, they were sorely lacking and high quality books were bought instantly.

Magazine Science and Life (Russian: Наука и Жизнь) cover

World War II finished this development. Many magazines were closed. In 1942, Ya. Perelman died of starvation in Leningrad. But non-fiction continued to live. Professor-lichenologist V. Savich working alone for the entire editorial office, firstly in the besieged Leningrad, and then in the evacuation published the magazine Priroda. Science and Life was reduced twice in copies, but nevertheless it continued to be published.

Popular science books were printed: The emergence of life on Earth by A. Oparin — 1941, Reflexes of the brain by I. Sechenov — 1942, The eye and the sun. About light, sun and vision by S. Vavilov — 1944, The Flora of the Ocean by N. Voronikhin — 1945, The History of Roman Literature by M. Pokrovsky — 1945, Archimedes by S. Lurie — 1945. Evacuated to Kazan, the Academy of Sciences published several books on the 300th anniversary of I. Newton.

Book covers dedicated to Newton,1943

It was at this time, 1943–1944, that the state scientific and technical policy was formulated. It became the basis for the future system of popularization of science. On September 27, 1944, the Central Committee issued a decree «On the organization of scientific and educational propaganda», and on December 14, 1944, in the Izvestia — an article by S. Vavilov «The duty of the Soviet intellectuals» was published. The destroyed Soviet Union urgently needed qualified personnel.

Golden age

Industrial and science lands was built with our labour hands

The war showed that it is not dashing head-on attacks that won, but accuracy, resiliency and maintainability. It was a «war of engines». The «space race» and the «arms race» that began after the war demanded scientific achievements. In July 1945 S. Vavilov was elected as a president of the USSR Academy of Sciences. In 1947 the Znanie society was created, its goal was the mass education of the population. The state finally approved the system of popularization of science and made it an obligatory part of scientific activity.

The release of popular science literature grew progressively. New magazines appeared: Young Technician — 1956, Model Designer — 1962, Science and Humanity — 1965, Chemistry and Life — 1965, Earth and the Universe — 1965, Quant — 1970. In total, about 83 popular science magazines were published in the USSR. They created a good competition environment, the editors made experiments, used unusual illustrations, released science fiction. The circulation of Nauka i zhizn reached 3 million per year, and in 1977 it published a draft of a new constitution of the USSR.

Books by Perelman were republished by millions of copies, the series of From the history of world culture, History and modern times, History of science and technology, Pages of the history of our Motherland, Nations of the world, Present and future of Earth and humanity, Man and the Environment, Science to Agriculture, Science and Technical Progress, Scientific and Atheistic Series, Scientific Biographies and Memoirs of Scientists, From Molecule to Organism, Planet Earth and the Universe and many others. In the 1980s, the Publishing House of the Academy of Sciences of the USSR, being renamed to Nauka, was the largest scientific publisher in the world. But it was then that the same thing happened as 70 years ago with political literature: the country was tired of mass propaganda.

Crisis

Political mistakes were replaced by economic ones and vice versa: the chance to become a global scientific research institute was irretrievably lost, industry was in stagnation, living standards collapsed, and talented scientists preferred countries with stable research funding. The population turned its attention to fiction and mysticism, and the state counted on religion.

Non-fiction literature collapsed. The surviving magazines have reduced the circulation by a hundred times, and the books turned out to be not in demand. Nauka became a typical state monopoly over the entire academic press and was on the verge of bankruptcy. The Znanie society collapsed, and the attempt to breathe new life into it reminds necromancy with the creation of zombie.

But there were local successes on this field. Computer technology magazines such as Computerra (1992), Byte (1998), CHIP (2001) appeared. And in the 90s, Quantum magazine was published in the USA with translations from Quant.

In the 2000s, despite the inaction of the state and the general crisis of publishing, the situation began to improve gradually. New magazines appeared: Popular Mechanics — 2002, First-hand Science — 2004, Machines and Mechanisms — 2005, Science and Technology — 2006, >Funny Quant — 2012,

Schrödinger’s Cat — 2014.

Funny Quant cover.

Suddenly it turned out that in the 21st century without R&D it is impossible to move forward, and due to this reason scientific community began to revive. Private publishing houses gradually translate foreign authors, reprint Soviet ones, new writers again appear: M. Gelfand, Asya Kazantseva, A. Raygorodsky, L. Podymov. Of course, it is a drop in the ocean, but…

It is not so bad, don’t be in fall.

We live in an interesting age: the education system does not keep pace with progress, and the huge demand for self-education is compensated by information technology. Cyberleninka, Sci-hub, Habr.com, Anthropogenesis.ru, Postnauka, Simplescience.ru, Elementy.ru, N+1, Naked Science took the place of the Academy of Sciences and made scientific content really affordable. And most importantly: they made it interesting. Large technology companies create editorial offices and, in fact, are engaged in «technical propaganda». Amateurs translate articles from foreign sources in great volumes. The areas in which Russians are traditionally strong are popularized: mathematics, physics, programming, biology.

As a result, Russian-language Internet is filled with high-quality and affordable foreign scientific content that falls on the powerful Soviet heritages. A paradoxical situation has turned out: due to the failure of traditional publishing houses, digital resources that generate high-quality content receive an impetus to development. Russian non-fiction literature is a famous brand with a rich history and it is alive and competitive. It remains only to wait for it to finally cope with the crisis and enter the world market.

P.S. Translated by Daria Sazonova